- Home

- Ovarian cancer

- About ovarian cancer

About ovarian cancer

Below we discuss what ovarian cancer is, the different types, who gets it, what causes it, and more.

Learn more about:

For your community

Overview

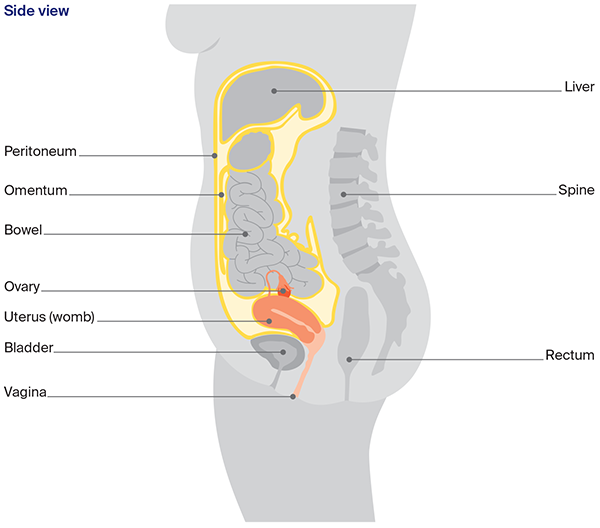

Ovarian cancer starts when cells in one or both ovaries, the fallopian tubes or the peritoneum become abnormal, grow out of control and can form a lump called a tumour. Cancer of the fallopian tube was once thought to be rare, but research suggests that many ovarian cancers start in the fallopian tubes.

If ovarian cancer spreads from the ovaries, it is often to the organs in the abdomen and pelvis. It is common in some types of ovarian cancer for a large amount of fluid to build up in the abdomen (belly).

Sometimes an ovarian tumour is diagnosed as a borderline tumour (also known as a low malignant potential tumour). This tumour is not considered to be cancer but can still spread within the abdomen (see the types of ovarian cancer).

The ovaries

The ovaries are part of the female reproductive system, which also includes the fallopian tubes, uterus (womb), cervix (the neck of the uterus), vagina (birth canal) and vulva (external genitals).

Ovaries are made up of:

- epithelial cells – found on the outside

- germ (germinal) cells – inside, these mature into eggs

- stromal cells – forming connective tissue and making hormones.

| What the ovaries do | The ovaries produce eggs. They also make the hormones oestrogen and progesterone, which control the release of eggs (ovulation) and the timing of periods (menstruation). |

| Shape and position in the body | The ovaries are 2 small, walnut- shaped organs. They are found in the lower part of the abdomen (belly). There is one ovary on each side of the uterus, close to the end of each fallopian tube. |

| Ovulation and menstruation | During ovulation, from puberty through to menopause, one ovary – or occasionally both – releases an egg. The egg travels through the fallopian tube to the uterus. If a pregnancy does not occur, some of the lining of the uterus is shed and flows out of the body. This flow is called a period or menstruation. |

| Menopause | As you get older, the ovaries gradually make less oestrogen and progesterone. When levels of these hormones fall low enough, periods stop. This is known as menopause. After menopause, you can’t have a child naturally. |

The female reproductive system

Organs and structures near the ovaries

Other organs and structures near the ovaries include the:

- bladder – stores urine (pee)

- bowel – helps the body break down food

- rectum – stores faeces (poo)

- peritoneum – lining of the abdomen

- omentum – a curtain of fatty tissue that hangs in front of the large bowel like an apron.

What are the different types of ovarian cancer?

There are many types of ovarian cancer. The 3 main types start in different cells found in the ovary.

|

Epithelial |

|

|

Stromal cell (or sex cord-stromal tumours) |

|

|

Germ cell |

|

Non-cancerous ovarian tumour

Borderline tumour

- abnormal cells that form in the tissue covering the ovary

- doesn’t grow into the supportive tissue (stroma)

- grows slowly

Who gets ovarian cancer?

Each year, about 1785 women are diagnosed with ovarian cancer in Australia. This includes cancers of the fallopian tube. More than 8 out of 10 women diagnosed are over the age of 50, but ovarian cancer can occur at any age. It is the 9th most common cancer in females in Australia.

Ovarian cancer mostly affects women, but anyone with ovaries can get it. Transgender men and intersex people can also get ovarian cancer if they have ovaries. For information specific to you, speak to your doctor.

For an overview of what to expect during all stages of your cancer care, visit Ovarian cancer – your guide to best cancer care. This is a short guide to what is recommended, from diagnosis to treatment and beyond.

What causes ovarian cancer?

The causes of ovarian cancer are largely unknown, but things that can increase the risk of developing ovarian cancer include:

- age – ovarian cancer is most common over the age of 50 after periods have stopped. The risk increases with age

- genetic factors – up to 1 in 5 serous ovarian cancers (the most common subtype) are linked to an inherited faulty gene, and a smaller proportion of other types of ovarian cancer are also related to genetic faults

- family history – having close blood relatives (e.g. mother, sister) diagnosed with ovarian, uterine, breast, bowel or uterine cancers, or having Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry can increase risk

- endometriosis – this is a condition caused by tissue from the lining of the uterus growing outside the uterus

- reproductive history – women who have not had children, who have had assisted reproduction (e.g. in-vitro fertilisation or IVF), or who have had children after the age of 35 may be slightly more at risk

- lifestyle factors – some types of ovarian cancer have been linked to smoking or carrying extra weight

- hormonal factors – for example, early puberty or late menopause. Some studies have suggested that menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) – formerly called hormone replacement therapy (HRT) – may slightly increase the risk of ovarian cancer if taken for 5 years or more, but the risk is very low.

Some factors may reduce the risk of developing ovarian cancer. These include having children before the age of 35; breastfeeding; using the combined oral contraceptive pill for several years; and having your fallopian tubes tied (tubal ligation) or removed.

Does ovarian cancer run in families?

Ovarian cancer most often occurs for unknown reasons but some cases are due to an inherited faulty gene. Having an inherited faulty gene does not mean you will develop ovarian cancer, and you can inherit a faulty gene without a history of cancer in your family.

About 15% of women with ovarian cancer have an inherited fault in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes or other similar genes. The BRCA gene faults can also increase the risk of developing breast cancer and fallopian tube cancer.

Less commonly, a group of gene faults known as Lynch syndrome is associated with ovarian cancer and can also increase the risk of developing cancer of the bowel or uterus.

As other genetic conditions are discovered, they may be included in genetic tests for cancer risk.

For more on this, listen to our podcast on genetic tests and cancer below.

→ READ MORE: Ovarian cancer symptoms

Podcast: Genetic Tests and Cancer

Listen to more of our podcast for people affected by cancer

More resources

Dr Antonia Jones, Gynaecological Oncologist, The Royal Women’s Hospital and Mercy Hospital for Women, VIC; Dr George Au-Yeung, Medical Oncologist, Peter MacCallum Centre, VIC; Dr David Chang, Radiation Oncologist, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, VIC; Prof Anna DeFazio AM, Sydney West Chair of Translational Cancer Research, The University of Sydney, Director, Centre for Cancer Research, The Westmead Institute for Medical Research and Director, Sydney Cancer Partners, NSW; Ian Dennis. Consumer (Carer); A/Prof Simon Hyde, Head of Gynaecological Oncology, Mercy Hospital for Women, VIC; Carmel McCarthy, Consumer; Quintina Reyes, Clinical Nurse Consultant – Gynaecological Oncology, Westmead Hospital, NSW; Deb Roffe, 13 11 20 Consultant, Cancer Council SA.

View the Cancer Council NSW editorial policy.

View all publications or call 13 11 20 for free printed copies.