- Home

- About Cancer

- Cancer treatment

- Clinical trials and research

- Clinical trials explained

- Randomised controlled trials

Randomised controlled trials

Learn the importance of randomised controlled trials in clinical research and how they help test if treatments work.

Learn more about:

- Overview

- What are randomised controlled trials (RCTs)?

- How randomisation works

- What are non-randomised trials?

- Standard treatment and placebos

- Blinded and crossover studies

Overview

It is important for researchers to know that the results of a study are accurate and not caused by chance. This means they must follow strict guidelines.

Researchers also need to make sure their own – or the participants’ – ideas or beliefs about the research don’t unfairly influence the results. There are various ways to make sure clinical trials are fair and reliable.

What are randomised controlled trials (RCTs)?

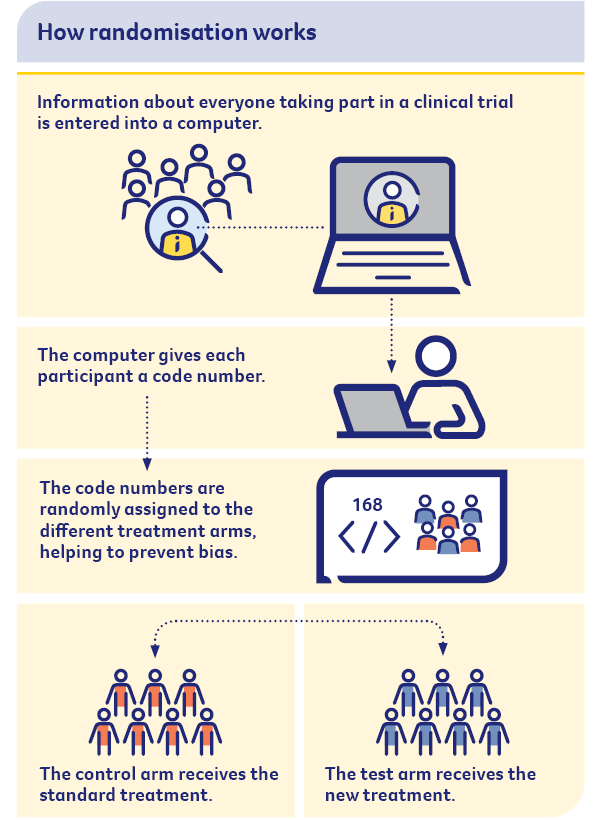

Many clinical trials are randomised controlled trials (RCTs). A randomised controlled trial helps prevent bias, so it is the best way to test if a new treatment works. (Bias occurs when the results of a trial are affected by human choice, expectations or other factors not related to the treatment being tested.)

Most phase 3 trials and some phase 2 trials are randomised. This means participants in the study are put into two or more groups (known as treatment arms) at random. The two groups then receive different treatments, and the results of the different groups are compared.

Researchers cannot choose who goes into each group.

| Test or experimental arm | This group is given the new treatment that is being tested. Sometimes, the experimental treatment is given in addition to the current standard treatment. |

| Control arm | This group receives the current standard treatment for the disease or an inactive treatment known as a placebo. |

When randomly allocated groups are compared with each other, it is possible to work out which treatment is better. This is because researchers can be certain that the results are related to the treatment, and not to any other factors (see also Blinded studies).

How randomisation works

What are non-randomised trials?

In a single arm trial, everyone receives the same experimental treatment. This method is known as a non-randomised trial. It may be used for phase 1 and phase 2 trials, or where the cancer being treated is rare and it is hard to conduct a randomised trial.

→ READ MORE: Standard treatment and placebos

Video: What are clinical trials?

In this video, Medical Oncologist Dr Elizabeth Hovey explains what clinical trials are and how they can improve cancer treatment.

Podcast: Making Treatment Decisions

Listen to more episodes from our podcast for people affected by cancer

More resources

All updated content has been clinically reviewed by A/Prof Brett Hughes, Senior Staff Specialist, Medical Oncology, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital and The Prince Charles Hospital, and Associate Professor, The University of Queensland, QLD. This edition is based on the previous edition which was reviewed by the following panel: A/Prof Brett Hughes (see above); Christie Allan, Clinical Trials Lead, Cancer Council Victoria, VIC; Dawn Bedwell, 13 11 20 Consultant, Cancer Council Queensland, QLD; Joanne Benhamu, Senior Research Nurse, Team Lead, Lung, Colorectal and Palliative Care Trials, Parkville Cancer Clinical Trials Unit, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, VIC; Louise Dillon, Consumer; Sabina Jelinek, Clinical Nurse Research, St John of God Murdoch Hospital, WA; Chloe Jennett, Program Coodinator, Cancer Research, Cancer Council NSW; Carmel McCarthy, Consumer; Alison Richards, Research Unit Manager, Medical Oncology Clinical Trials Unit, Flinders Medical Centre, SA; Prof Jane Ussher, Translational Health Research Institute (THRI), School of Medicine, Western Sydney University, NSW; Prof Janette Vardy, Medical Oncologist, Concord Cancer Centre, and Professor of Cancer Medicine, The University of Sydney, NSW.

View the Cancer Council NSW editorial policy.

View all publications or call 13 11 20 for free printed copies.