- Home

- About Cancer

- Cancer treatment

- Targeted therapy

- Gene changes and cancer cells

Gene changes and cancer cells

Discover the role of gene changes in the development of cancer. Learn how acquired gene mutations can contribute to the formation of tumors.

Learn more about:

- Overview

- Testing for targeted therapy

- Family testing

- Paying for tests

- Some gene changes linked to cancer

Overview

Genes are made up of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid). Each human cell has about 20,000 genes, and most genes come in pairs, with one copy inherited from each parent. As well as telling the cell what to do and when to grow and divide, genes provide the recipe for cells to make proteins. These proteins carry out specific functions in the body.

When a cell divides, it makes a copy of itself, including all the genes it contains. Sometimes copying mistakes can happen, causing changes (mutations or alterations) in the genes. If these mistakes affect the genes that tell the cell what to do, a cancer can grow.

Acquired vs. inherited gene changes

Most gene changes that cause cancer build up during a person’s lifetime (acquired gene changes). Some

people are born with a gene change that increases their risk of cancer (an inherited faulty gene, also known as hereditary cancer syndrome). Only about 5% of cancers are caused by an inherited faulty gene.

Targeted therapy drugs may act on targets from either acquired or inherited gene changes. See the table below for examples of both types of gene changes.

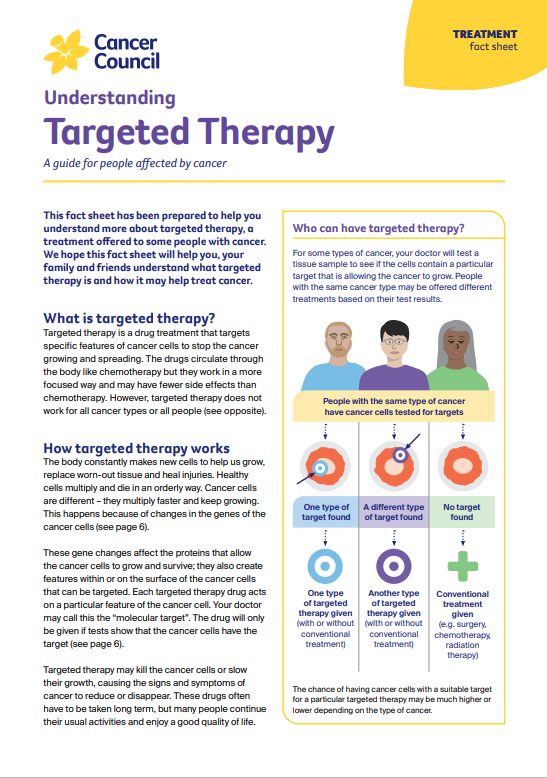

Testing for targeted therapy

To find out if the cancer contains a gene change that may respond to a particular targeted therapy drug, your doctor will take a sample from the cancer or your blood, and send it to a laboratory for testing. It may take from a few days to a few weeks to receive the results.

The testing may find specific mistakes in that cancer, whether they are acquired gene changes found only in the cancer cells, or inherited changes that are also present in normal cells. The testing may involve a simple test known as staining, or more complex tests known as genomic or molecular testing.

Family testing

If the cancer contains a faulty gene that may be linked to a hereditary cancer syndrome, or if your personal or family history suggests a hereditary cancer syndrome, your doctor will refer you to a family cancer service or genetic counsellor. They may suggest genetic testing.

Knowing that you have inherited a faulty gene may help your doctor work out what treatment to recommend. It could also allow you to consider ways to reduce the risk of developing other cancers, and it is important information for your blood relatives. Medicare rebates are available for some genetic tests. You may need to meet certain eligibility requirements.

If you are concerned about your family risk factors, talk to your doctor or ask for a referral to a family cancer clinic. To find out more, call Cancer Council 13 11 20 or visit www.genetics.edu.au to find a public family cancer clinic.

Will I have to pay for these tests?

Medicare rebates are available for some genetic tests. You may need to meet certain eligibility requirements and usually the tests must be ordered by a specialist. For more information about genetic testing, talk to your specialist or family cancer clinic, or call 13 11 20.

Some gene changes linked to cancer

Acquired gene change |

Linked to these cancers* |

| ALK mutations | lung, neuroblastoma |

| BRAF mutations | melanoma, bowel, lung, thyroid |

| BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations (acquired) | ovarian |

| EGFR mutations | lung |

| IDH mutations | brain, bile duct |

| KRAS mutations | bowel, lung, pancreatic |

| NRAS mutations | bowel, lung, pancreatic |

| HER2 mutations (including gene overexpression) | breast, stomach, lung, bowel |

| KIT mutations | gastrointestinal stromal tumours, melanoma |

| MET mutations | lung |

| NTRK alterations | brain, lung, breast, bowel, sarcoma |

| RET alterations | thyroid, lung |

| ROS1 alterations | Thyroid, lung |

*May be involved in other cancers, but list includes the main cancers linked to these gene changes.

Inherited gene change |

Increases the risk of these cancers |

| BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations (inherited) | breast, ovarian, pancreatic, prostate |

| Cowden syndrome | breast, thyroid, uterine |

| familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) | bowel, stomach, thyroid |

| Li-Fraumeni syndrome | breast, primary bone, adrenal |

| Lynch syndrome | bowel, brain, hepatobiliary, kidney, pancreatic, ovarian, skin, stomach, uterine, urinary tract |

Podcast: Immunotherapy & Targeted Therapy

Listen to more episodes from our podcast for people affected by cancer

Video: What is targeted therapy?

Watch this short video to learn more about drug therapies, including targeted therapy and immunotherapy.

More resources

A/Prof Rohit Joshi, Medical Oncologist, Calvary Central Districts and Lyell McEwin Hospital, and Director, Cancer Research SA; Jenny Gilchrist, Nurse Practitioner – Breast Oncology, Macquarie University Hospital, NSW; Jon Graftdyk, Consumer; Sinead Hanley, Consumer; Lisa Hann, 13 11 20 Consultant, SA; Dr Malinda Itchins, Thoracic Medical Oncologist, Royal North Shore Hospital and Chris O’Brien Lifehouse, NSW; Gay Refeld, Clinical Nurse Consultant, Breast Care, St John of God Subiaco Hospital, WA; Prof Benjamin Solomon, Medical Oncologist, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, VIC; Helen Westman, Lung Cancer Nurse Consultant, Respiratory Medicine and Sleep Department, Royal North Shore Hospital, NSW

View the Cancer Council NSW editorial policy.

View all publications or call 13 11 20 for free printed copies.