- Home

- Liver cancer

- Treatment

- Radiation therapy: SBRT and SIRT

Radiation therapy

In this section we look at using radiation therapy to treat primary liver cancer.

Learn more about:

- Overview

- Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT)

- Selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT)

- Video: What is radioembolisation or SIRT?

Overview

Primary liver cancer is sensitive to radiation but so are healthy liver cells. Two specialised techniques can deliver radiation directly to the tumour while limiting the damage to the healthy part of the liver.

These are called stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) and selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT). SBRT may be suitable for people with early-stage cancer, while SIRT may be offered in more advanced cases.

Conventional external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) is also occasionally used as a palliative treatment to help manage symptoms. For example, short courses of EBRT can help to control pain caused by liver cancer that has spread to the bones.

Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT)

This type of therapy may be called stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) or stereotactic ablative body radiation therapy (SABR). It is a type of external beam radiation therapy. The machine precisely targets beams of radiation from many different angles onto the tumour.

SBRT is prescribed by a radiation oncologist and delivered in a radiation therapy department. This method allows a high dose of radiation to be delivered to the tumour while surrounding healthy tissue is protected from the effects of radiation. SBRT requires fewer treatment sessions than conventional radiation therapy. People may need only 3–8 sessions over one or two weeks.

This treatment may be offered to people with tumours that can’t be removed with surgery or treated with tumour ablation or TACE. SBRT may also be used to shrink tumours while people are waiting for a liver transplant.

What happens before the treatment?

Before this treatment, you will have a CT scan and maybe an MRI scan as well. These scans help make an individual plan for your treatment. You may also need a short procedure to insert small metal markers (called fiducial markers) next to the tumour.

These markers allow the radiation oncologist to monitor the exact position of the tumour during the treatment. They are usually made of gold and are about the size of a grain of rice. A needle is used to put in the markers during the CT scan. Not all people will need to have these markers inserted.

How SBRT is done

Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) precisely targets beams of high-dose radiation from different angles onto the tumour.

What happens during the treatment?

During treatment, you will be asked to lie on a treatment table while a machine delivers the targeted beams to the tumour. It is important to lie very still during SBRT treatment. Simple breathing techniques – like holding your breath for 10–15 seconds – can help reduce movement during the procedure. Your treatment team will talk to you about this.

SBRT itself is painless, and you can usually go home after the treatment. You will not be radioactive after SBRT.

Selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT)

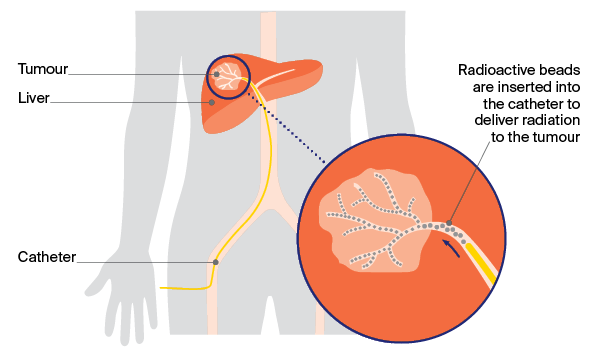

Selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT) is a different type of radiation therapy. Sometimes called radioembolisation, SIRT combines embolisation (which blocks blood supply to the tumour) with internal radiation, where the radiation source is placed inside the liver.

In SIRT, the radiation is delivered through the blood vessels to the tumour using tiny radioactive beads, which are made of resin or glass.

The procedure may be offered for primary liver cancer when the tumours can’t be removed with surgery or to shrink tumours before a liver resection or a transplant.

SIRT is performed by an interventional radiologist, supported by a nuclear medicine physician, in a radiology department. One to two weeks before the procedure, you will have a work-up day to ensure the procedure is appropriate for you.

Work-up day

Several tests will be done on this day, including blood tests to check kidney function and blood clotting, and an angiogram (an x-ray of the blood vessels).

Before the angiogram, you will have a local or general anaesthetic. The interventional radiologist will then make a small cut in the groin area and insert a thin plastic tube (called a catheter) into the artery that feeds the liver (hepatic artery). A small amount of dye (contrast) will be passed through the catheter into the bloodstream. On an x-ray, the dye provides a detailed map of the blood supply to the liver, which varies from person to person. The doctor may also block some small blood vessels. This helps to stop the radioactive beads travelling beyond the liver to other parts of the body when you have the SIRT treatment.

Next, a substance called a radiotracer will be injected into the catheter and you will have another scan. This scan shows where the radioactive beads will go on the day of treatment. It will also check if any beads are likely to travel to the lungs. This step helps the doctor work out if it is safe to go ahead with the treatment.

Treatment day

On the day of treatment, you will have another angiogram. The interventional radiologist will make a cut in the groin area and pass a catheter through to the hepatic artery.

The radioactive beads will be inserted through the catheter into the hepatic artery. These beads can then deliver radiation directly to the tumour.

The procedure takes about an hour. You will be monitored after the procedure, and recover in hospital overnight.

How SIRT is done

Selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT) combines embolisation with internal radiation therapy (see above for a description of the treatment day).

After treatment

You may develop flu-like symptoms, nausea and pain, which can be treated with medicines. You can usually go home within 24 hours.

The radioactive beads will slowly release radiation into the tumour over the next week or so. During this time, you may need to take some safety precautions such as avoiding close physical contact with children or pregnant women. You may also be advised to not share a bed or have sex in the first few days after treatment.

→ READ MORE: Transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE)

Video: What is radioembolisation or SIRT?

Dr Simon So explains how radioembolisation or SIRT is used to treat liver cancer.

Podcast: Making Treatment Decisions

Listen to more episodes from our podcast for people affected by cancer

A/Prof Simone Strasser, Hepatologist, AW Morrow Gastroenterology and Liver Centre, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital and The University of Sydney, NSW (clinical update); A/Prof Siddhartha Baxi, Radiation Oncologist and Medical Director, GenesisCare, Gold Coast, QLD (clinical update); Prof Katherine Clark, Clinical Director of Palliative Care, NSLHD Supportive and Palliative Care Network, Northern Sydney Cancer Centre, Royal North Shore Hospital, NSW; Anne Dowling, Hepatoma Clinical Nurse Consultant and Liver Transplant Coordinator, Austin Health, VIC; A/Prof Koroush Haghighi, Liver, Pancreas and Upper Gastrointestinal Surgeon, Prince of Wales and St Vincent’s Hospitals, NSW; Karen Hall, 131120 Consultant, Cancer Council SA; Dr Brett Knowles, Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary and General Surgeon, Royal Melbourne Hospital, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre and St Vincent’s Hospital, VIC; Lina Sharma, Consumer; David Thomas, Consumer; Clinical A/Prof Michael Wallace, Department of Hepatology and Western Australian Liver Transplant Service, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital Medical School, The University of Western Australia, WA; Prof Desmond Yip, Clinical Director, Department of Medical Oncology, The Canberra Hospital, ACT.

View the Cancer Council NSW editorial policy.

View all publications or call 13 11 20 for free printed copies.